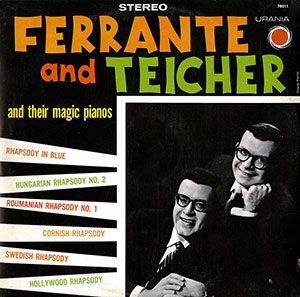

Rhapsody

- Charles Wildman: Swedish Rhapsody

- Georges Enesco: Roumanian Rhapsody in A Major, Op. 11, No. 1

- Franz Liszt: Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2

- Hubert Bath: Cornish Rhapsody

- George Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue

- Ferrante & Teicher: Hollywood Rhapsody

Lp released in 1955 and reissued with various album covers.

Lp (mono): Urania URA-78011

Lp (simulated stereo): Urania 78011

Lp (simulated stereo): Urania US 58011

Rhapsody

Musical rhapsodies have been in existence for a little more than a hundred years. They are still a flourishing form, firmly entrenched in popular favor. They personify the bombastic, showy side of Romanticism just as the variously called bagatelles, preludes, nocturnes, moments musicaux, and songs without word represent the lyric and intimate side. The rhapsody was meant for the public concert hall which catered to all levels of musical development; the brief lyrics were for the private salon and more discriminating ears. Rhapsodies tend to have one movement unified by the repetition of several themes or of a single idée fixe; these weave their way through contrasting moods and scenes which in the earliest dynamic models suggested action-packed vigor, the fires of national pride, a sense of yearning for the past, unquenchable joie de vivre, etc. The very word “rhapsody” (supposedly used in this sense first by Liszt in 1853) gave notice, according to its derivation-melodies that are joined to one another—that it was operating on a wider charter of musical license than a symphony or concerto; it set out to break traditional architectural patterns and it substituted for them a fantasia-like surge of emotions divided into a series of separate cantos or musical chapters. It was the voice of the Romantic artist when he struck the epic note. He identified himself with a folk figure of a whole people who struggled, as he individually was struggling in his art, to be free and untrammeled. Roaming freely over its material, the rhapsody highlights the art of a single instrument (for example, the cello in Bloch’s Shelomo or the piano in Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue) or it shows off the virtuoso technique of a huge orchestra. Everything about it used to be larger than life. Hence its style was in the grand manner, charged with tension and expressed in high-flown rhetoric. Its creators were the nineteenth century breed of composer-performers — theatrical creatures, with Lisztian heads of hair or the saturnine melancholy of a Paganini, who graphically re-emoted the agonies of creation with each performance.

It is no accident that national tags are attached to rhapsodies, as for example: Liszt (Hungarian), Ravel (Spanish), Alfven (Swedish), Bloch (Hebrew), Hovhaness (Armenian), etc. These works originally came into being in the last century at a time when political struggles for unification or independence were sweeping across Europe. They were also an outgrowth of the Romantic’s sudden delighted appreciation of the uniqueness of his country’s natural setting, folk accents, glorious past, and aspirations for the future.

Sometimes a Romantic composer preferred to call his work a tone poem or symphonic poem, but the difference between these and rhapsodies was often slim. Thus, nostalgic descriptive material such as Smetana’s My Fatherland, Borodin’s Steppes of Central Asia, or Sibelius’ Finlandia may well be called rhapsodic. By the twentieth century, the fires of nascent nationalism had died down. Rhapsodies (now often called suites) came to be written merely as glorifications of local color e.g. Grofe’s Grand Canyon, Mississippi River, and Hudson River Suites; Gould’s Latin-American Rhapsody and Cowboy Rhapsody. Where the Lisztian type of rhapsody relied on poetic and historic associations, the modern descendant tended to lean on the art of painting — tonal painting of a highly realistic order. Also, it turned its back on the past to concentrate as does Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue (1924) on a new musical idiom characteristic of the composer’s own time. Modern rhapsodies seem not to involve the emotions of the composer too deeply. They are written in conservative style (for which the average music lover is infinitely grateful) and they content themselves with being pleasantly atmospheric rather than probing the distinctive differences of the locales they are describing. In this category belong the late Hubert Bath’s Cornish Rhapsody and Ferrante and Teicher’s Hollywood Rhapsody.

For the archetype of the virtuoso rhapsody, one must turn to Liszt’s Fifteen Hungarian Rhapsodies of which No. 2 has been twice orchestrated — once by Liszt and once by Karl Müller-Berghaus. The two sections contain the characteristic lassu and friss — slow and quickstep of the Hungarian czardas. Liszt here is following the musical patterns made familiar by Hungarian gypsies whom he mistakenly regarded as transmitters of authentic Hungarian folk music. In its orchestral dress, the work becomes a showpiece for orchestra like Enesco’s Roumanian Rhapsody in which prominence is given successively to the flute, viola, oboe, and clarinet. In this sprightly work, as Enesco himself tells us, gypsy influence is stronger than that of the neighboring Slavs.

Bernard Lebow

The Artists

ARTHUR FERRANTE and LOUIS TEICHER, two enterprising pianists, have fused their talents to produce a new commodity in the world of music and sound. They tailor a wide variety of concert, semi-classic, and pop compositions to their instruments, an on occasion, to ginger up pop selections, they even tinker with their instruments to produce novel sound effects. In serious repertory, however, they cut no capers. There they are noted for lucidity, precision, adaptability to many styles of music, and fingers that are fleet far beyond the ordinary. In the past ten years, they have come to be admired by countless thousands on nation-wide concert tours, on radio and TV, and on several notable record releases. Their clever arrangements of Brahms, Schumann, Debussy, Saint-Saens or of Porter, Kern, etc. endow familiar compositions with new vitality and enriched sonorities. As for the various ways in which they “prepare” the piano for pop programs, they justify their innovations by maintaining that historically “the piano contains its ancestors — harp, lute, dulcimer, zither, clavichord, and harpsichord,” and they are only attempting to bring these submerged sonorities to the fore. Although only in their thirties, Ferrante and Teicher have appeared as performers of serious music with the New York Philharmonic, Rochester Symphony, Detroit Symphony, Toledo Symphony, and New York City Symphony Orchestras. On the air waves, in serious as well as light classics, listeners have heard them regularly on ABC’s Piano Playhouse, NBC’s Eddie Dowling Show, or NBC’s Carnation Hour. Sophisticated m.c.’s such as Steve Allen, Garry Moore, Ernie Kovacs, and Mitch Miller have been proud to introduce them on their TV shows. In all these media, they have received rave notices for their through mastery of their craft, their versatility, and the artistic rapport which transforms them into a single artistic entity. In their arrangements and in their piano style, they provide excitement in the modern manner. They are ideally suited to the diablerie which is the breath of life to most rhapsodies.

ARTHUR FERRANTE and LOUIS TEICHER, two enterprising pianists, have fused their talents to produce a new commodity in the world of music and sound. They tailor a wide variety of concert, semi-classic, and pop compositions to their instruments, an on occasion, to ginger up pop selections, they even tinker with their instruments to produce novel sound effects. In serious repertory, however, they cut no capers. There they are noted for lucidity, precision, adaptability to many styles of music, and fingers that are fleet far beyond the ordinary. In the past ten years, they have come to be admired by countless thousands on nation-wide concert tours, on radio and TV, and on several notable record releases. Their clever arrangements of Brahms, Schumann, Debussy, Saint-Saens or of Porter, Kern, etc. endow familiar compositions with new vitality and enriched sonorities. As for the various ways in which they “prepare” the piano for pop programs, they justify their innovations by maintaining that historically “the piano contains its ancestors — harp, lute, dulcimer, zither, clavichord, and harpsichord,” and they are only attempting to bring these submerged sonorities to the fore. Although only in their thirties, Ferrante and Teicher have appeared as performers of serious music with the New York Philharmonic, Rochester Symphony, Detroit Symphony, Toledo Symphony, and New York City Symphony Orchestras. On the air waves, in serious as well as light classics, listeners have heard them regularly on ABC’s Piano Playhouse, NBC’s Eddie Dowling Show, or NBC’s Carnation Hour. Sophisticated m.c.’s such as Steve Allen, Garry Moore, Ernie Kovacs, and Mitch Miller have been proud to introduce them on their TV shows. In all these media, they have received rave notices for their through mastery of their craft, their versatility, and the artistic rapport which transforms them into a single artistic entity. In their arrangements and in their piano style, they provide excitement in the modern manner. They are ideally suited to the diablerie which is the breath of life to most rhapsodies.

I have two "stereo" copies of the Lp on the Urania label. One has a black cover displaying a photo of F&T (Urania 78011, no prefix); the other (still-sealed) has the white cover shown above on US 58011 (UR 58011 on the spine).

On the right is yet another album cover which I suspect might be the one used when the Lp was originally released: