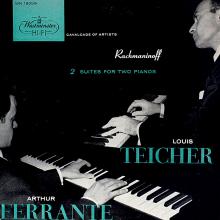

Rachmaninoff Two-Piano Suites

- Suite No. 1 for Two Pianos, Op. 5 (Fantasy): Barcarole / "Oh night, oh love" / Tears / Russian Easter

- Suite No. 2 for Two Pianos, Op. 17: Introduction / Waltz / Romance / Tarantella

Lp released in 1955.

Lp (mono): Westminster XWN-18059

THE MUSICSergei Rachmaninoff’s two Suites for Two Pianos were both relatively early works by the noted composer-conductor-pianist, but their musical content differs considerably, as did the circumstances under which they were written.

The First Suite, Op. 5, called Fantasia by Rachmaninoff, dates from the summer of 1893, when the composer was only twenty. He spent the summer with friends on a country estate in the Government of Kharkov, enjoying immensely the respite the fresh country air afforded him after a winter in his modest quarters in Moscow. The fertile southern earth brought forth not only the rich fruits of nature but also several promising works from the young musician. In addition to the Suite—or Fantasia—he produced that summer two pieces for violin and piano, Op.6; the Fantasia for Orchestra The Rock, Op. 7, and a lengthy Sacred Concerto.

Before leaving for the country, he had written his Five Pieces for Piano, Op. 3, which were published shortly after their completion. The third of these pieces if the famous Prelude in C sharp Minor, which brought him rapid and far-flung recognition.

Returning to Moscow in the fall, Rachmaninoff visited his former teacher, Teneiev, where he encountered another friend, adviser and ardent supporter—Tchaikovsky. What transpired at that meeting is related in Rachmaninoff’s Recollections, as told to Oskar von Riesemann. Tchaikovsky was much impressed with the success of the Prelude, as well as with the considerable amount of music his young colleague had managed to turn out during the summer. “And I, miserable wretch,” he remarked, “have only written one Symphony!” That symphony, the last work to come from his pen, was the Pathétique.

At this meeting, Rachmaninoff told Tchaikovsky that he was dedicating his Fantasia for Two Pianos to him, whereupon the older man asked to hear it. But Rachmaninoff wisely refused; though he considered it his best work to date, he feared for its effect if performed on only one piano. He told Tchaikovsky that he planned to give the Fantasia a concert performance in Moscow that same autumn, and the latter promised to attend the premiere. In place of the Fantasia that evening, Rachmaninoff played The Rock, and Tchaikovsky was so delighted with it that he said he would include it on the programs he was to conduct on his European tour that winter.

Included in Rachmaninoff’s immediate plans was a trip to Kiev to direct several performances of his opera Aleko. As he took his leave, Tchaikovsky said, “This is how famous composers part from one another! The one goes to Kiev to conduct his opera, the other to St. Petersburg to conduct his Symphony!” A few weeks later, Tchaikovsky was dead, a victim of cholera.

The Suite No. 1 for Two Pianos represents Rachmaninoff’s first attempt at writing program music. Not only is it dedicated to Tchaikovsky but it also reflects a great deal of his musical influence. The definitive Rachmaninoff stamp is not yet affixed to this work, though there are many passages which are unmistakably characteristic and prophetic, while the technical, tonal and interpretive resources of the two keyboards have been employed with masterly insight. The work is in four movements, headed by verses from Lermontov (who also inspired The Rock), Byron, Tyoutchev and Khomiakov. The movements are entitled, respectively, Barcole, “Oh Night, Oh Love,” Tears, and Easter. The first movement is warm and romantic; the second and third rather melancholy, and the finale is a short, exuberant carillon, a wonderful imitation of the bells of the Kremlin ringing out on Easter morning. Rachmaninoff and Moussorgsky must have heard those bells with ears similarly attuned, for there is a marked affinity between the Easter movement of this Suite and the sound of the bells in the great Coronation Scene from Boris Godounoff, which also takes place before the Kremlin.

Whereas the First Suite was inspired by a stay in the Russian countryside, the Second Suite, Op. 17, may be said to have been born in a psychiatrist’s office. Rachmaninoff’s First Symphony, bearing the fateful opus number 13, had been a failure at its premiere in St. Petersburg in 1897, and he immediately suppressed it, hiding the score and parts. The work was not performed again until two years after his death. But its failure left an indelible imprint upon the sensitive young composer; already subject to moodiness, he fell into a state of melancholy brooding and apathy, which lasted for three years, during which time he composed nothing.

Finally, his cousins, the Satins, with whom he was living, induced Rachmaninoff to visit Dr. Nicolai Dahl, a practitioner in the science of hypnosis and auto-suggestion, and himself an amateur musician. Between January and April, 1900, he paid daily visits to the doctor’s office where, sitting half-asleep in a chair, he listened to the same words, repeated over and over again: “You will begin to write your Concerto. . . . You will work with great facility. . . . The Concerto will be of an excellent quality. . . .” The reason for the insistence upon a concerto was that Rachmaninoff had promised to compose his Second Piano Concerto for presentation in London, but had been unable to make any progress of it.

The plan worked. Dr. Dahl’s psychiatric treatment started Rachmaninoff back on the road to creating new music. Before long, he not only had enough ideas for his Concerto but there was sufficient material left over for his Suite No. 2 for Two Pianos, which was completed in 1901 and published before the Concerto. Other works came forth in quick succession, too; these included the Sonata for Cello and Piano, Op. 19; the Cantata Spring, Op. 20; twelve songs, Op. 21; the Variations for Piano on a Theme of Chopin, Op. 22, and the Preludes, Op. 23.

Considering the fact that it took root in Rachmaninoff’s mind simultaneously with the Second Piano Concerto, it is not at all surprising that the Second Suite for Two Pianos sounds as if it had been cut from the same cloth. Thematically and harmonically, then, it is much more typical of its composer than the First Suite. Like the latter, it is in four movements, surprisingly of a more cheerful character, however. The first movement is a robust Introduction; the second—and most popular—is a lilting Valse; the third an extremely lyrical Romance, and the fourth a brilliant Tarantella, which recalls more than any of its companion sections the style and mood of the Second Concerto.

PAUL AFFELDER

THE ARTISTFerrante and Teicher began their astonishing career as duo pianists when they met at the age of six at New York’s Juilliard School of Music, where they shared the distinction of being two of the youngest students to have been accepted by that famous school. Following their graduation and after a period of concertizing, they both returned to teach at Juilliard, and to continue their work of enlarging, augmenting and creating new duo-piano material. Their programs, combing classics and intricate arrangements of popular tunes, have found favor with audiences far and wide, The Ferrante and Teicher “Vanette”—a special truck holding two grand pianos—has become a familiar sight on America’s transcontinental highways, speeding these two artists to their engagements. Besides many radio performances, they have also received critical acclaim for their New York recitals and appearances with The New York Philharmonic, The Rochester, Detroit and Toledo Symphony Orchestras.

THE RECORDThis recording is processed according to the R.I.A.A. characteristic from a tape recorded with Westminster’s exclusive “Panorthophonic”® technique. To achieve the greatest fidelity, each Westminster record is mastered at the same level technically suited to it. Therefore, set your volume control at the level which sounds best to your ears. Variations in listening rooms and playback equipment may require additional adjustment of bass and treble controls to obtain NATURAL BALANCE. Play this recording only with an unworn microgroove stylus (.001 radius). For best economical results we recommend that you use a diamond stylus, which will last longer than other needles. Average playback times: diamond—over 2000 plays; sapphire—50 plays; osmium or other metal points—be sure to change frequently. Remember that a damaged stylus may ruin your collection.