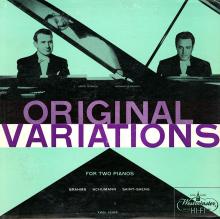

Original Variations for Two Pianos

- BRAHMS: Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56 b

- SCHUMANN: Andante and Variations, Op. 16

- SAINT-SAENS: Variations on a Theme by Beethoven, Op. 35

Lp released in 1955.

Lp (mono): Westminster XWN-18169

THE MUSICThe classical variation form reached its highest peak in the work of Beethoven. In Haydn and Mozart, variations consisted primarily in the presentation and mere ornamentation of theme—richly, to be sure. But Beethoven in his Thirty-Two Variations in C minor and in the Eroica Variations, while adding new content, reaches back into the great contrapuntal technique of Bach, making use of the basso ostinato (the continually recurring bass pattern) as exemplified in Bach’s Goldberg Variations, the D minor Chaconne and the majestic C minor Passacaglia. In the Diabelli Variations, Op. 120 we see how Beethoven, out of a most unlikely theme, creates a work which, though based on the theme, is independent of it and completely transcends it. Schubert’s variations are hardly less imaginative and resourceful.

With Weber there emerges the virtuoso variations, the variation which, in later hands, becomes the mold over which are poured ever-increasingly shallow decorations. Even during Beethoven’s lifetime this degeneration is at work, witness Czerny’s endless, superficial embellishment of themes, a procedure which has at least the excuse of a pedagogical purpose. The Paris solons, however, are deluged with pianist-composers—Kalkbrenner, Thalberg, Herz, Hünten and Moscheles—who spin out their millions of arpeggios and scales, “showers of pearls” as the admiring Parisian critics lovingly called them. Theirs is a mass production in identical design of “Grandes Variations,” “Variations difficiles,” “faciles,” “de bravour” or “sur un air favori” —the last generally based on tunes form Bellini, Donizetti or Meyerbeer operas. Trailing after thunderous introductions having, as a rule, little or nothing to do with the innocent themes they preface, these variations glitter like paste jewels and culminate in a blaze of digital wizardry.

As critic, Schumann deplored the dearth of artistry in these “manufactured” pieces. In the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik of which he was editor, he tore their shabbiness to tatters, remarking that such rubbish ought to find its destiny in a fiery furnace. Yet he was not merely destructive. Variations, he adds, should be constructed on a simple, forthright theme, should complement the theme and grow out of it, and build into a unified work of which the theme is the cornerstone. They should be such that the theme, unadorned, could be set in the middle or at the end. The introduction should prepare the listener for the ensuing thematic content, and the finale must sum up the entire work, not weaken it by mere brilliant show. Above all, the variation must contain ideas. He terms Beethoven’s variations “ideal artistic works” and Schubert’s “the most finished of artistic paintings.” He held Chopin in high esteem, remarking that his variations could have been composed by Schubert or Beethoven, had they been piano virtuosos.

SCHUMANN: Adante and Variations

As composer, Schumann led the way to reform in his own Symphonic Etudes, Abegg Variations and others. Even the lovely Papillons and Carnaval, though not variations, use the form.

The Adante and Variations in B flat, Op. 46 were originally written for two pianos, two cellos and horn. A short introduction preceded the theme. After the first rehearsal Schumann withdrew the piece, feeling that the setting was unsatisfactory, and changed it into its present two-piano form. He may have also thought that in a less complex form it might have more chances of performance. It was first publicly performed by Clara Schumann and Mendelssohn in 1844. Clara and Brahms played it in Vienna in 1868. The original setting was published in Schumann’s collected work in 1893.

The theme is graceful, fluent, the entire work having great rhythmic and melodic variety. The ornamental figures are not of the hackneyed unimaginative kind, but ingenious, arresting, as well as decorative. Here and there Schumann creates lovely, new melodic lines to the basic harmonies of the theme. An overuse of antiphony between the two pianos sometimes leads to a kind of monotony, but the work as a whole does not lack invention, by any manner or means.

BRAHMS: Variations on a Theme by Haydn

An even greater role is played by the variation form in the compositions of Brahms. He wrote prolifically to themes of Handel, Paganini, Schumann, as well as to Hungarian dance melodies and themes of his own. The finale of his Fourth Symphony in E minor stands as one of the crowning glories in this genre. He not only created beautiful, complex variations, but went still further by fashioning variations built on previous variations, new melodies of haunting charm, virile rhythms, never employing ornament for ornament’s sake.

Carrying the contrapuntal variation even further than Beethoven, he sometimes did not even adhere to the bass and harmonies, though the general structure of the theme is always adumbrated. Real pianists and musicians are needed to recreate his compositions adequately for they are truly difficult. Here is no fake technical brilliance. The Paganini Variations are the only ones written from the virtuoso point of view, and even they are not flimsy, but highly artistic solutions of knotty technical problems.

For his Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op 56b Brahms chose the subject of the second movement of Haydn’s Feldpartita in B flat. It is an old Burgenland pilgrims’ chant, called Chorale St. Antonii. Solid and straightforward, it lends itself excellently to variations.

Brahms ha probably intended the work for orchestra, since its orchestral version is labelled Op. 56a, but according to biographers, he wrote the two-piano version first. He must have worked very hard on it, as elaborate preliminary sketches for the piece—unusual for Brahms—are to be found in the library of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna. Certainly each section shows the effects of careful craftsmanship and inspiration, and its finale, built on a basso ostinato, is masterful.

SAINT-SAENS: Variations on a Theme by Beethoven

A short prelude, tentatively touching on the theme of Beethoven which follows, introduces Saint-Saens’ Variations on a Theme by Beethoven, Op. 35 based on the trio from the minuet in Beethoven’s E flat Sonata, Op. 31, No. 3. The piece is stylish, suave, characteristically Saint-Saens. Its smooth, rather facile piano figurations take it back to the typical middle 19th century variation genre. But it has points of interest, what with its C minor funeral march, its fugue of ample proportions, albeit of usual contrapuntal devices, and its presto-scherzo modulating from E flat to E. Cultivated, refined, though not a masterwork, it is a grateful piece pianistically.

SAM MORGENSTERN

THE ARTISTSFerrante and Teicher began their astonishing career as duo pianists when they met at the age of six at New York’s Juilliard School of Music, where they shared the distinction of being two of the youngest students to have been accepted by that famous school. Following their graduation and after a period of concertizing, they both returned to teach at Juilliard, and to continue their work of enlarging, augmenting and creating new duo-piano material. Their programs of the classical repertoire have found favor with audiences far and wide. They have also gained an enviable following for their intricate arrangements of popular tunes. The Ferrante and Teicher “Vanette”—a special truck holding two grand pianos—has become a familiar sight on America’s transcontinental highways, speeding these two artists to their engagements. Besides many radio performances they have also received critical acclaim for their New York recitals and appearances with leading symphony orchestras in this country.

THE RECORDThis recording is processed according to the R.I.A.A. characteristic from a tape recorded with Westminster’s exclusive “Panorthophonic”* technique. To achieve the greatest fidelity, each Westminster record is mastered at the volume level technically suited to it. Therefore, set your volume control at the level which sounds best to your ears. Variations in listening rooms and playback equipment may require additional adjustment of bass and treble controls to obtain NATURAL BALANCE. Play this recording only with an unworn microgroove stylus (.001 radius). For best economical results we recommend that you use a diamond stylus, which will last longer than other needles. Average playback times: diamond—over 2000 plays; sapphire—50 plays; osmium or other metal points—be sure to change frequently. Remember that a damaged stylus may ruin your collection.

___________

* Registration pending